Singleton vs Dependency Injection

This post is a showcase for the Singleton design pattern. In contrast to the common belief, Singleton is not inherently bad and I’ll try to show you in what circumstances it is a good choice.

Singleton

Let me give a refresher regarding what Singleton is about. It is one of the most basic design patterns from the GoF book and I’m sure most of you knows it, but it’s still a good place to start.

Singleton is a design pattern which stands for having only one instance of some class during the whole application lifetime. A typical implementation of a Singleton looks like this:

public class BankGateway

{

public readonly static BankGateway Instance = new BankGateway();

private BankGateway()

{

}

public void TransferMoney()

{

/* Transferring money */

}

}

Note that the constructor is private and the only way to get an instance of it is to refer to the Instance property. And as this property is static, it will live for as long as the application process is still running (more precisely, it’s bound to the application domain lifetime).

Also, note that this implementation doesn’t support lazy loading, so the instance will be instantiated at the type load regardless of whether you need it or not. (Actually, the behavior is more complex and depends on the presence of the beforefieldinit IL flag for that class, which in turn depends on the specific .NET Framework version and the existence of a static constructor. These details are not essential for us.) And of course, we can easily implement a version that supports lazy loading.

The main complaint about Singleton is that it contradicts the Dependency Injection principle and thus hinders testability. It essentially acts as a global constant, and it is hard to substitute it with a test double when needed.

So, if you have a method like this one:

public class Processor

{

public void Process()

{

BankGateway.Instance.TransferMoney();

}

}

It would be difficult to test it because each time you run the Process method, it calls the actual bank gateway. And that is something we should avoid during unit tests execution.

Dependency Injection

Dependency Injection is a design pattern that stands for passing dependencies to objects using them. The code above can be rewritten using this pattern in the following way:

public interface IBankGateway

{

void TransferMoney();

}

public class BankGateway : IBankGateway

{

public void TransferMoney()

{

/* Transferring money */

}

}

public class Processor

{

private readonly IBankGateway_gateway;

public Processor(IBankGateway gateway)

{

_gateway = gateway;

}

public void Process()

{

_gateway.TransferMoney();

}

}

The code above is testable. We can create a fake bank gateway, pass it to the Processor and make sure it uses it to transfer money. At the same time, no calls to the actual bank gateway are made.

Singleton vs Dependency Injection

The latter design is preferable in the vast majority of cases. If you’ve got a non-stable dependency, it’s always a good practice to inject that dependency to the dependent class. Aside from greater testability, this practice helps the class explicitly specify everything it needs in order to perform properly. A non-stable dependency is a dependency which refers to or affects the global state, such as external service, file system, or a database.

However, there still are dependencies which are better represented using Singleton. They are ambient dependencies. Ambient dependencies are dependencies which span across multiple classes and often multiple layers. They act as cross-cutting concerns for your application.

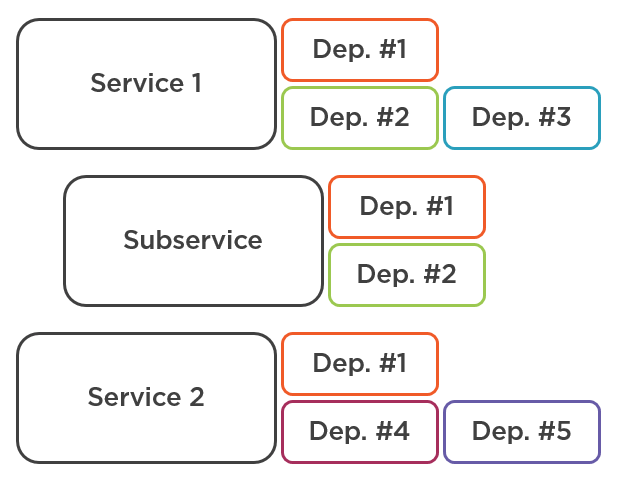

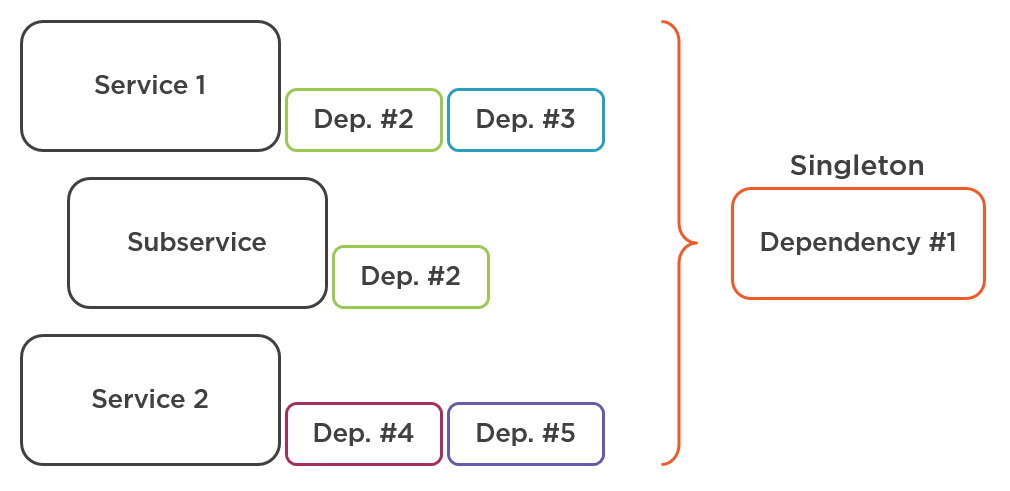

It doesn’t really make sense to apply the Dependency Injection design pattern for such dependencies as they are going to be everywhere anyway. Here’s how we can diagram one:

The dependency #1 is present in each of the three services. Hence, it’s a good candidate for extracting it to a Singleton:

What we are doing here is we are essentially removing that dependency from the "dependency equation" making the overall graph simpler. Without doing this, the code base would be flooded with the excessive number of the same dependencies traversing most of your classes.

The heuristic to determine whether you need to introduce a singleton is simple. If a dependency cross-cuts most of your classes and/or several layers in your application, extract it using the Singleton pattern. Otherwise, use the standard Dependency Injection technique. The ultimate goal is to make sure that you don’t use DI for ambient dependencies.

Singleton examples

A good example here is a logger service. If you tend to log a lot of activities throughout your code base, it’s just not practical to pass the logger instance to every class that needs it as a dependency. A better way is to introduce a Singleton.

Another example is the DateTime.Now property. It’s often the case that you want to fake it in unit tests to make sure your code works with current date and time correctly. However, wrapping this functionality in a dependency and injecting it all over your code base would turn it into a mess. Singleton is a viable option here as well.

So instead of code like this:

public interface ISystemDateTime

{

DateTime Now { get; }

}

public class SystemDateTime : ISystemDateTime

{

public DateTime Now

{

get { return DateTime.UtcNow; }

}

}

// Implement a fake SystemDateTime and pass it in unit tests

You can introduce a static class in the following way:

public static class SystemDateTime

{

private static Func<DateTime> _func;

public static DateTime Now

{

get { return _func(); }

}

public static void Init(Func<DateTime> func)

{

_func = func;

}

}

// Initialization code for production

SystemDateTime.Init(() => DateTime.UtcNow);

// Initialization code for unit tests

SystemDateTime.Init(() => new DateTime(2016, 5, 3));

Here, Instead of passing around instances of the ISystemDateTime interface, we make the SystemDateTime class static and define an Init method in it that accepts a factory for producing the current date and time. We then use different factories for test and production environments.

Note that such implementation leaves a whole in our code base as we need not forget to initialize Singletons before using them. In other words, we introduce a temporal coupling here. However, it’s pretty easy to track an error in case you forget to initialize a Singleton as it would show up close to the application start-up. And it’s still cleaner than passing huge amount of repeating dependencies all over your code base. Moreover, as all such initializations are usually gathered in a single place - Composition Root - it’s pretty easy to manage them anyway.

Ultimately, you need to reach a balance between dependencies injected using the DI principles and the ones introduced as singletons. You don’t want ambient dependencies to be passed around as they would flood your dependency graph. At the same time, you don’t want to represent occasional dependencies as Singletons.

Domain singletons

A separate type of singletons which I also would like to mention here is the one which is intrinsic to your domain model. Sometimes, a concept just fits the Singleton pattern even if it’s not an ambient dependency. For example, if you have an Organization entity and there can be only one such entity in your domain model, it’s just fine to represent it as a Singleton as well:

public class Organization

{

public static OrganizationInstance { get; private set; }

private Organization(int id, string name)

{

/* ... */

}

public static void Init(int id, string name)

{

Instance = new Organization(id, name);

}

}

Summary

It’s important to keep a balance between the dependencies represented as Singletons and the ones injected using the DI principles. The following heuristic will help you to determine which pattern to use:

-

If a dependency is ambient, meaning that it is used by many classes and/or multiple layers, use Singleton.

-

Otherwise, inject it to the dependent classes using the Dependency Injection pattern.

Subscribe

Comments

comments powered by Disqus