Temporal coupling and Immutability

This topic is partly covered in my Applying Functional Principles in C# Pluralsight course, Module 2. Here, I’d like to elaborate on how temporal coupling and immutability are related to each other.

Temporal coupling

Temporal coupling is coupling that occurs when there are two or more members of a class that need to be invoked in a particular order. A common example is the following:

var calculator = new PriceCalculator();

calculator.UpdateCurrencyRates(eur: 1.02, gbp: 1.25);

decimal price = calculator.CalculatePrice(myShoppingCart);

Here, currency rates are required to calculate the price of a shopping cart. Without it, the CalculatePrice method throws an exception. However, neither the signature of the method nor the constructor’s signature force you to supply the rates. You need to remember to do that yourself. As a result, these two methods - UpdateCurrencyRates and CalculatePrice - are coupled together with temporal coupling: they have to be invoked in this exact order to avoid runtime errors. At the same time, nothing in the class’s API gives you a hint about what that order might be. Such design heavily relies on the human factor and thus is quite error-prone.

The fix is simple in this case. We just need to make the currency rates mandatory:

var calculator = new PriceCalculator(eur: 1.02, gbp: 1.25);

decimal price = calculator.CalculatePrice(myShoppingCart);

Now there’s no need to remember anything, the constructor forces you to provide the required data.

Temporal coupling and Immutability

Immutability is a guideline saying that once created, a class instance should not be changed. Any modifications are handled by creating new instances rather than mutating existing ones.

There’s a deep relationship between these two concepts. To see it, let’s consider the following code sample:

public class CustomerService

{

private Address _address;

private Customer _customer;

public void Process(string customerName, string addressString)

{

CreateAddress(addressString);

CreateCustomer(customerName);

SaveCustomer();

}

private void CreateAddress(string addressString)

{

_address = new Address(addressString);

}

private void CreateCustomer(string name)

{

_customer = new Customer(name, _address);

}

private void SaveCustomer()

{

var repository = new Repository();

repository.Save(_customer);

}

}

This class gets a name and an address string as input parameters and uses them to add a new customer to the database.

Just as the previous code sample, this one has a major drawback: the invocations in the Process method are coupled in the temporal dimension. For this code to work properly, we need to remember which method depends on what to always call them in the right order:

public void Process(string customerName, string addressString)

{

CreateAddress(addressString); // Updates _address

CreateCustomer(customerName); // Needs _address, updates _customer

SaveCustomer(); // Needs _customer

}

If we mess up with that order, the code will fail at runtime. For example, if we put the second method call above the first one:

public void Process(string customerName, string addressString)

{

CreateCustomer(customerName); // Needs _address

CreateAddress(addressString);

SaveCustomer();

}

then the method wouldn’t get the required dependency - address - and the resulting customer instance will become invalid.

Likewise, if we try to put the SaveCustomer method invocation before others, it will throw a null reference exception: at the time it tries to save a customer, the customer instance would still be null.

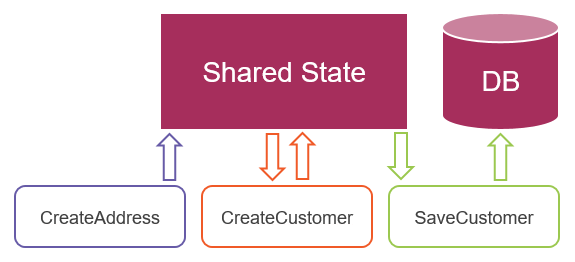

What we have here is essentially this:

All three methods write to and read from the shared mutable state. And that is exactly what fosters the temporal coupling. In fact, without a shared state, temporal coupling becomes impossible! The solution to this problem boils down to getting rid of that state. Making things immutable, in other words.

Below is a new version of the same code:

public class CustomerService

{

public void Process(string customerName, string addressString)

{

Address address = CreateAddress(addressString);

Customer customer = CreateCustomer(customerName, address);

SaveCustomer(customer);

}

private Address CreateAddress(string addressString)

{

return new Address(addressString);

}

private Customer CreateCustomer(string name, Address address)

{

return new Customer(name, address);

}

private void SaveCustomer(Customer customer)

{

var repository = new Repository();

repository.Save(customer);

}

}

Note how we’ve removed the private fields. Getting rid of the shared state automatically decoupled the three methods and made the workflow explicit. Without the shared state, the only way we can carry data around is by using the methods' arguments and return values. And that is exactly what we did: all three members now explicitly state required inputs and possible outputs in their signatures.

This is the essence of functional programming. With honest method signatures, it’s extremely easy to reason about the code as we don’t need to keep in mind hidden relationships between its different parts. It’s also impossible to mess up with the invocation order. If we try, for example, to put the second line above the first one, the code simply wouldn’t compile:

public void Process(string customerName, string addressString)

{

// Compilation error: address is not yet defined

Customer customer = CreateCustomer(address);

Address address = CreateAddress(addressString);

SaveCustomer(customer);

}

The only piece of shared state left here is the database: the SaveCustomer method persists the customer at the end of the workflow. Which is basically fine because it’s impossible to get rid of all mutations in your code. Just try to adhere to the "sandwich" design pattern: push the work with shared state to the edges of your business operations (Mutable Shell) and keep the stuff in-between immutable (Functional Core). I wrote more about this kind of architecture in this post: Immutable architecture.

There’s an important guideline that follows from the above. Look at the following code:

public void SomeMethod()

{

Operation1();

Operation2();

Operation3();

Operation4();

}

While it looks clean and simple, such design is almost never a good choice. The only use case where it’s applicable is when you have some background job firing once in a while and all operations in it are unrelated to each other. In all other cases what you’re actually doing here is hiding the relationships between these methods behind some shared state.

It’s better to write down those relationships explicitly, like so:

public void SomeMethod()

{

var result1 = Operation1();

var result2 = Operation2(result1);

var result3 = Operation3(result1, result2);

var isOperation4Required = IsOperation4Required(result3);

Operation4(isOperation4Required);

}

It’s more code and thus might feel less clean, but this way you will have much easier time tracking down what the method actually does. The previous version required the reader to examine each of its parts separately in order to see what pieces of shared state they use and modify. This version shows the workflow right away; there’s no need to step into any of the private methods. The code also doesn’t suffer from temporal coupling anymore: it’s impossible to mess up with the invocation order because the compiler keeps it in check. Getting rid of shared state and temporal coupling works wonders.

Private methods and signature honesty

I’d like to mention one important technique that is related to this topic. Look at the following class:

public class PriceCalculator

{

private readonly CurrencyRates _currencyRates;

public PriceCalculator(CurrencyRates rates)

{

_currencyRates = rates;

}

public MoneyCalculatePrice(Cart cart)

{

Money priceInDollars = CalculatePriceInDollars(cart.Items);

Money finalPrice = ConvertCurrency(priceInDollars);

return finalPrice;

}

private Money ConvertCurrency(Money priceInDollars)

{

/* Use _currencyRates to calculate the price */

}

}

Its CalculatePrice method looks pretty good. The two private methods it uses explicitly define what they accept and return; the workflow is quite obvious here too. There’s one thing, though, we can still improve in this code. Note that the ConvertCurrency private method uses the currencyRates field to calculate the final price. Instead of referring to this field, the method can declare an additional argument, like so:

private Money CalculatePrice(Cart cart)

{

Money priceInDollars = CalculatePriceInDollars(cart.Items);

Money finalPrice = ConvertCurrency(priceInDollars, _currencyRates);

return finalPrice;

}

private Money ConvertCurrency(Money priceInDollars, CurrencyRates rates)

{

/* Use rates to calculate the price */

}

This way, we are converting it into a mathematical function. It doesn’t refer to the shared state anymore; its method signature is now completely honest about its inputs and outputs. Of course, it might be troublesome to do that with all private methods but sometimes it makes sense not to refer to the shared state even if that state is private. Mathematical functions have quite a few benefits in terms of readability, so this technique is worth considering.

Summary

-

Temporal coupling and immutability are inherently related to each other. Without shared state, it’s impossible to couple methods in the temporal dimension.

-

By bringing in immutability, you automatically get rid of temporal coupling.

-

Try to always define inputs and outputs of your methods explicitly, even if those methods are private.

-

Try not to refer to shared state, even if this state is private.

See also

Subscribe

Comments

comments powered by Disqus